Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The search for two missing siblings six-year-old Lily Sullivan and her four-year-old brother Jack, missing since May 2 in rural Pictou County, Nova Scotia, has entered its sixth day with no breakthroughs.

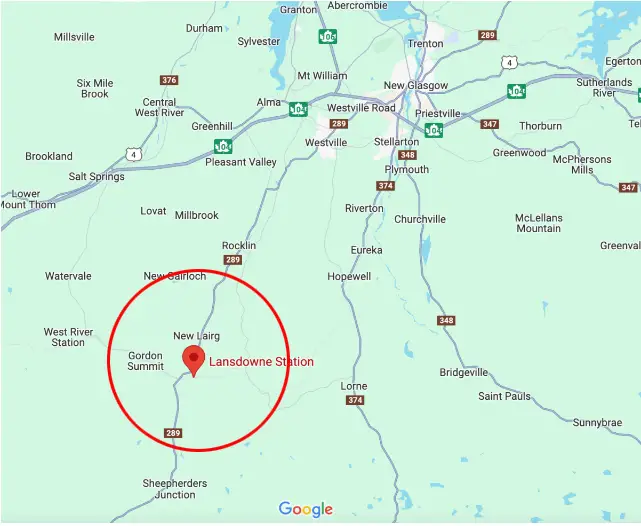

Imagine waking up to find two of your children vanished without a trace. That’s the reality gripping Daniel Martell and his partner, Malehya Brooks-Murray, whose blended family has been thrust into a waking nightmare. On the morning of May 2, Lily Sullivan, a bubbly six-year-old with a strawberry-themed backpack, and her shy four-year-old brother Jack slipped out of their Lansdowne Station home through a sliding door Martell describes as “virtually silent.” The siblings, who’d stayed home from school due to Lily’s cough, were last seen wearing colorful outfits—Lily in pink boots and Jack in blue dinosaur shoes.

“They hate being wet and cold. If they’d just wandered off, they’d have come back,” Martell told reporters, his voice breaking. “But there’s nothing—just one set of footprints near the road.” The family’s rural property, surrounded by dense woods still littered with debris from Hurricane Fiona, has become ground zero for a search operation that’s drawn hundreds of volunteers, drones, and even helicopters.

For six grueling days, teams have combed through a 4 km² radius around the Sullivan home. Colchester County Ground Search and Rescue coordinator Amy Hansen described the effort as “like fighting a forest with your bare hands.” Fallen trees from Fiona’s 2022 rampage block paths, while swampy areas and thick undergrowth slow progress. “We’ve had searchers waist-deep in water, crawling over deadwood,” Hansen said. “People are exhausted, getting cuts, sprains—but no one’s quitting.”

The RCMP’s high-tech arsenal—thermal drones, heat-sensing helicopters, and cadaver dogs—has turned up nothing. A single boot print found Saturday initially sparked hope, but it led nowhere. “We’ve tagged every searched tree with orange markers,” Hansen explained. “From the air, it looks like the woods are dotted with autumn leaves. We’ve left no stone unturned.”

The lack of an Amber Alert has fueled public frustration. Martell insists, “If someone offered them candy or said ‘Let’s find Mom,’ they’d get in a car.” But RCMP Staff Sgt. Robert McCamon, head of the major crimes unit, remains adamant: “There’s zero evidence of abduction. No tire marks, no stranger sightings, no digital footprints.”

Here’s the thing: Amber Alerts in Canada require proof of abduction. Without it, police issued localized “vulnerable missing person” (search for two missing siblings) alerts to Pictou County phones. Critics argue the system needs flexibility. “A four-year-old in the woods is as urgent as a kidnapping,” said Halifax child safety advocate Marcie DeLaney. “But protocols are protocols.”

The emotional weight of the search is crushing. Volunteers, many parents themselves, return each day with haunted expressions. “You look at their photos and think, ‘That could be my kid,’” said volunteer firefighter Tom Carter, his boots caked in mud. “We’re all running on coffee and adrenaline.”

For the family, the agony is unbearable. Brooks-Murray has temporarily moved in with relatives, while Martell paces their empty home. “I keep replaying that morning,” he said. “Was the door locked? Did I check the yard enough?” Community members from the nearby Sipekne’katik First Nation have organized prayer vigils and meal trains, but as days pass, the unspoken question looms: Are we searching for children or casualties?

On Wednesday, RCMP made the gut-wrenching call to transition from a “full-scale search” to targeted sweeps. “We’re not giving up,” Staff Sgt. Curtis MacKinnon stressed, “but we need to focus on areas with the highest probability.” Translation: They’re revisiting spots already checked, hoping to find clues missed in the chaos of early days.

Cadaver dogs may soon join the effort—a possibility MacKinnon called “the next logical step.” When pressed on survival odds, he didn’t sugarcoat it: “Six days in the wilderness? With nighttime temps near freezing? Realistically, hope’s fading.” Meteorologists confirm rain has drenched the area since May 3, dropping the “feels like” temperature to 2°C at night.

This tragedy exposes gaps in rural search protocols. Lansdowne Station, population 300, lacks the infrastructure of urban centers. “We’re using maps from 2018 because newer ones don’t exist,” admitted Hansen. Meanwhile, social media sleuths have spiraled into conspiracy theories, from alien abductions to witness protection programs—distractions that drain investigative resources.

Yet amid the darkness, glimmers of humanity shine. A GoFundMe for the family has raised over $80,000. Strangers from New Brunswick to Newfoundland have mailed stuffed animals to the RCMP detachment. “Lily loves unicorns, Jack adores dinosaurs,” read one note. “Please give these to them when they’re found.”

As official efforts wind down, civilian groups vow to keep looking. “We’ll hike until our legs give out,” vowed local guide Hank Tremblay. The RCMP continues to analyze phone pings and security footage from nearby Route 289, a quiet road Martell fears could’ve been used by predators.

For now, Lily’s pink boots and Jack’s dinosaur shoes remain symbols of a community’s fraying hope. As night falls over Pictou County, porch lights burn brighter than ever—a silent plea for two missing pieces of this rural puzzle to come home.

“They’d get in any car if offered candy or to see Mom and Dad.” — Stepfather Daniel Martell’s haunting plea underscores fears of abduction despite police ruling it out.

Note: The search remains active, though reduced in scope. Updates will follow if new evidence emerges.